Adverse Event Handling: Essential PI Guidelines

Adverse event handling is where good trials quietly become credible trials—or where “everything looked fine” turns into a safety reporting failure that haunts a PI during audits, publications, and sponsor oversight. The hard part isn’t knowing that AEs matter. The hard part is building a workflow that survives real clinic pace: incomplete source notes, late patient calls, unclear attribution, and a team that doesn’t know what to escalate. This PI-focused guide gives you a practical system for triage, documentation, timelines, and delegation—so safety stays compliant without burying your site in chaos.

1) Adverse Event Handling: The PI’s Real Job (Not the Myth)

Most PIs assume AE handling is “report what happens.” In reality, your job is to run a safety decision system that can withstand pressure and scrutiny. That means your site can consistently recognize an AE, capture it the same day, decide what it is (severity, seriousness, expectedness, relatedness), and route it correctly—without losing clinical meaning. If the process is vague, everything degrades: coordinators hesitate, documentation gets thin, and downstream pharmacovigilance teams are forced to guess. That’s where compliance breaks, not because your team is careless—but because the workflow is not designed.

The PI is ultimately accountable, but not because you should personally type every narrative. You’re accountable because you must ensure the team has a repeatable structure. Your coordinators need clarity on what qualifies as an AE, what is urgent, what is not an AE but still needs documentation, and how to escalate quickly. You also need alignment with monitoring expectations, because a CRA will test your safety system through source review and consistency checks. When you understand how monitoring pressure works—what CRAs flag, how they interpret gaps—you can build a site process that doesn’t collapse at the first monitoring visit. If you want a clean picture of what monitors look for, review the core signals in the CRA roles, skills & career path and how site execution is judged through CRC responsibilities & certification expectations.

AEs also don’t live in isolation—they touch protocol, endpoints, and data structure. If your CRF design doesn’t capture safety details cleanly, your team will record them inconsistently, and your database becomes unreliable during medical review. That’s why AE handling is inseparable from strong CRF practices like consistent definitions, minimal ambiguity, and clear “what goes where” rules described in the CRF definition, types & best practices. And if your primary endpoint has safety implications (or key secondary endpoints are safety-related), your documentation discipline must match the analytical stakes explained in primary vs. secondary endpoints, because endpoint-grade data requires endpoint-grade rigor.

Below is a PI-grade decision matrix you can use to standardize AE handling at your site, reduce “interpretation gaps,” and prevent the most common safety documentation failures that trigger monitoring findings and PV escalations. For deeper safety context and downstream reporting logic, keep the pharmacovigilance essential guide open while you implement this.

2) PI Triage That Holds Up: Severity vs Seriousness vs Relatedness (Without Confusion)

A PI’s safety judgment gets tested in two places: first by pharmacovigilance, who must transform your clinical story into structured regulatory reporting, and second by monitors and auditors, who look for internal consistency. The easiest way to lose credibility is not a rare complicated case—it’s routine confusion between severity and seriousness, or a causality call that lacks reasoning. If you want the clean conceptual backbone for how safety teams interpret your reports, anchor your site’s approach in the practical framing used in the pharmacovigilance guide, then translate it into behavior your CRCs can execute.

Severity is about intensity; seriousness is about outcome and criteria. That sounds simple until real life happens—when a “severe headache” is not serious, but a “moderate bleed” might be serious if it requires hospitalization. Your team needs a site script: when an AE is identified, the coordinator captures the narrative and immediately asks the seriousness screening questions so escalation is never delayed by uncertainty. That screening should be operationalized as a workflow, not a memory test, and it should be rehearsed just like protocol procedures. Your CRC’s role discipline matters here, because most safety misses happen at the intake step; revisit the execution expectations in CRC responsibilities and align them to how your CRA will pressure-test your source, as described in CRA roles and monitoring realities.

Relatedness is where PIs often under-document. “Not related” might be correct, but without reasoning it becomes fragile. A strong causality rationale reads like a clinician thinking out loud: timing relative to dosing, alternative etiologies, objective findings, response to treatment, and dechallenge information if available. If your protocol has blinding, your causality call becomes even more sensitive because bias and unblinding risks can creep into how events are interpreted and discussed. Even when your study is not primarily about blinding, the discipline of bias control described in blinding types and importance helps PIs keep safety assessment clinically grounded without drifting into assumptions about assignment or sponsor expectations.

Expectedness is another silent failure point because sites sometimes reference the wrong document version. If you treat expectedness as “someone else will handle it,” you invite downstream reclassification requests and follow-up queries from PV. Build a site rule that the CRC documents which reference was used and ensures version control is current, and treat this like regulatory discipline. That documentation hygiene pairs naturally with binder/TMF systems discussed in managing regulatory documents, because safety compliance is both clinical and administrative: your clinical decision must be defensible, and your filing must be provable.

3) Documentation That Survives Monitoring: Source, CRF, Narrative, and Reconciliation

Your site’s safety credibility is written in the space between three systems: the medical record/source, the CRF in EDC, and the safety reporting channel used by PV. Most “AE problems” are actually consistency problems: a date mismatch between source and EDC, an outcome recorded as “resolved” in one system but “ongoing” in another, or a medication started for an AE with no indication documented. These gaps feel small, but they create the worst kind of risk—risk that looks like sloppiness, even when the clinical care was excellent.

Start with source. A good AE source note is not long; it is complete. It captures the timeline, the clinical assessment, the key interventions, and what happens next. If the event is serious, you’re building a narrative that PV can use without chasing your site five times. Your CRF should mirror source logic, not fight it. If the CRF structure is confusing or encourages inconsistent entry, fix the process: clarify which fields are mandatory, define where supportive details live, and harmonize the language your team uses. That’s why PIs should care about CRF quality; the operational blueprint for clean, consistent capture is outlined in CRF best practices, and it directly reduces query burden and safety follow-ups.

Then there’s reconciliation, which is where sites silently lose time. If you do not maintain a simple safety tracking log (even if it’s internal and not sponsor-provided), you will miss follow-ups, forget outcomes, and fail to update ongoing AEs. Those misses become monitoring findings and delay database readiness. This is where the trial’s project management spine matters: you treat safety follow-ups like tasks with owners and due dates, not like “we’ll remember.” If you want a broader framework for how operational systems prevent downstream chaos, the principles in data monitoring committee oversight and workflows are useful even at the site level, because DMC-ready trials are trials that track, update, and reconcile safety information continuously rather than at the last minute.

One of the most overlooked documentation moves is linking AEs to the study’s clinical logic. If key safety outcomes relate to endpoints or secondary measures, the narrative must be consistent with the endpoint definitions and data expectations. That relationship is why high-performing sites train staff using endpoint examples, like those in primary vs. secondary endpoints, so coordinators understand what details actually matter for interpretation. When that clarity exists, your AE records stop sounding generic and start sounding clinically useful.

4) The PI Safety Operating System: Delegation, Oversight, and “No-Surprises” Execution

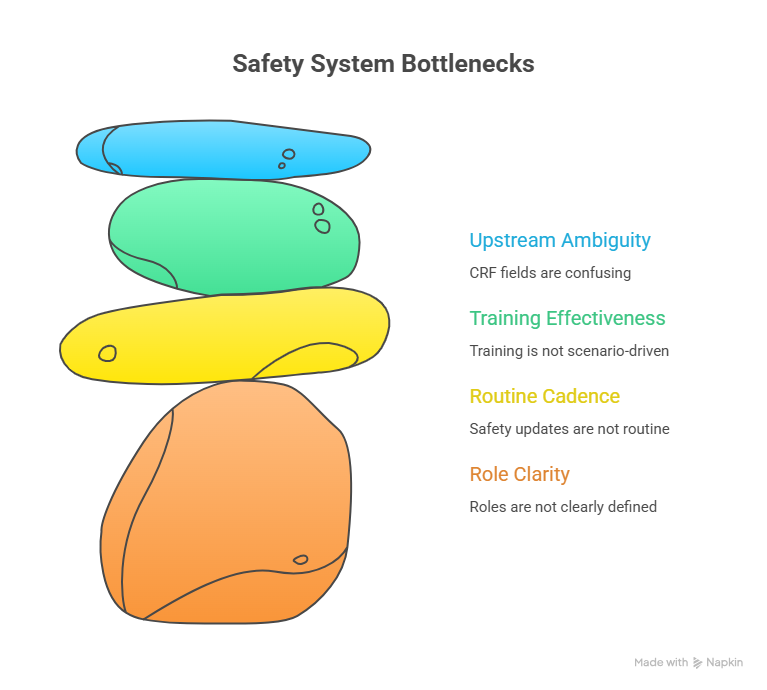

A PI who tries to personally “do safety” becomes a bottleneck; a PI who designs a safety operating system becomes a force multiplier. The system starts with role clarity. Your CRC should own intake capture and follow-up tracking; your regulatory coordinator should own filing discipline; your Sub-I or PI should own seriousness and relatedness decisions; and your team should know exactly when to escalate and how fast. When roles blur, events get delayed because everyone assumes someone else will decide.

The next layer is routine cadence. High-performing sites treat safety updates as a standing workflow, not as interrupt-driven emergencies. That means you have a weekly safety reconciliation touchpoint where ongoing AEs are reviewed for outcomes, missing records, and pending follow-ups. This is not “another meeting.” It’s a short, structured review that prevents late-stage chaos and protects the site during monitoring. This discipline also prevents the same operational mistakes that cause broader trial breakdowns; the site-level philosophy matches the governance logic seen in structured oversight frameworks like DMC workflows, because predictable cadence reduces last-minute risk.

Your system also needs training that sticks. If training is just a slide deck, behavior won’t change. The training must be scenario-driven: hospitalization events, lab abnormalities, baseline worsening, and patient calls after hours. Coordinators should practice writing a clean clinical summary that PV can use immediately, aligned with the clinical framing in the pharmacovigilance guide. When you train this way, your safety narratives stop being vague and start being decision-ready.

Finally, safety quality improves when you reduce upstream ambiguity. If CRF fields are confusing, your site will create mismatches and queries. If endpoints are unclear, your AE-related details will be inconsistent. If regulatory filing lacks structure, you’ll fail inspection readiness. That’s why PI-level safety maturity depends on fundamentals across the study: clean CRF structure (CRF best practices), clarity on what the study is actually measuring (endpoints clarified), and operational discipline in documentation systems (managing regulatory documents).

5) Inspection-Ready AE Handling: What Auditors, CRAs, and PV Actually Punish

Sites rarely “fail” safety because a patient had an adverse event. They fail because the record looks inconsistent, late, or unreasoned. CRAs will flag patterns: repeated late onset dates, missing action taken, outcomes never updated, causality assessments that appear random, and discrepancies between source and EDC. Those patterns tell a story: the site’s safety process isn’t controlled. If you want to understand why monitors focus on these gaps, reconnect your team to how monitoring is performed and what “good” looks like in CRA roles and monitoring expectations.

PV teams punish different failures: unclear narratives, missing timelines, lack of supporting documents for serious events, and inadequate follow-up. They’re not being difficult; they’re trying to meet regulatory reporting requirements and need your clinical clarity to do it. That’s why your PI decisions must be written, not implied, and why the underlying safety mechanics in the pharmacovigilance guide should inform your internal templates.

Auditors punish what cannot be proven. If your safety correspondence is not filed properly, if you can’t show follow-up attempts, if your documentation doesn’t demonstrate PI oversight, your site looks noncompliant even when care was excellent. The simplest path to inspection readiness is consistent filing discipline and controlled documentation routines, which is exactly what the workflow in managing regulatory documents is designed to support.

If your trial includes blinding, or randomization adds operational complexity, you also need to protect against subtle bias and procedural errors that can contaminate safety interpretation or trigger protocol deviations. The operational clarity in randomization techniques and the discipline required in blinding help PIs design safer, more consistent workflows—because in complex designs, small inconsistencies turn into big credibility issues fast.

6) FAQs: Adverse Event Handling for PIs (High-Value, Real-World Answers)

-

The most common mistake is late or incomplete capture—the event is discussed, treated, and even documented clinically, but not recorded in a consistent research-ready way with onset, action, assessment, and outcome. This creates source/EDC mismatches and follow-up churn that PV teams hate. Build your process using the clinical clarity framework in the pharmacovigilance guide and enforce consistent CRF mapping via CRF best practices.

-

Delegate intake capture and tracking to the CRC, but keep seriousness/relatedness decisions as PI/Sub-I responsibilities. Oversight is proven through consistent review cadence and signatures/attestations where required. This is easiest when roles mirror expectations described in CRC responsibilities and withstand monitoring scrutiny described in CRA roles.

-

Because serious event reporting often requires a complete clinical story, not just a label. PV needs dates, diagnostics, treatment, outcomes, and supporting records to classify and report correctly. If your narrative lacks a timeline, you’ll get repeated follow-ups. Align your narrative habits with the structure used in the pharmacovigilance guide.

-

Use a simple safety follow-up tracker and a weekly reconciliation routine. Most ongoing AEs are not truly “unknown”—they’re just not revisited. Treat outcomes like tasks with due dates and owners, and file evidence consistently using principles from managing regulatory documents.

-

Make source and EDC agree. That means your source note includes a clear assessment and the same core elements that the CRF requires, and your team follows a consistent rule for severity, seriousness, and relatedness. Monitors are trained to detect inconsistency; align to what they evaluate in CRA monitoring expectations and reduce form ambiguity using CRF best practices.

-

Blinding raises the risk of bias and accidental unblinding in how AEs are discussed, interpreted, and documented. Your site should use consistent scripts and role boundaries so safety assessment stays clinically grounded and doesn’t drift toward assumptions about assignment. The operational principles are outlined in blinding in clinical trials.

-

A one-page system includes: an intake script, seriousness screening questions, a causality rationale template, a follow-up tracker rule, and filing guidance. If you want the best reference anchors, use the pharmacovigilance guide for safety logic and managing regulatory documents for inspection-ready proof.