Primary vs Secondary Endpoints: Clarified with Examples

Primary vs Secondary Endpoints sound simple until a protocol gets amended, a site measures the wrong thing, or a sponsor realizes the “headline result” is not powered, not clean, or not clinically meaningful. Endpoints are the trial’s scoreboard. They decide what success means, how the sample size is calculated, how data is captured in the CRF, and how regulators and payers interpret the result. If your endpoint strategy is weak, the study can look “busy” while proving nothing. This guide clarifies the real difference between primary and secondary endpoints, shows how they behave in analysis, and gives practical examples you can reuse in protocols and monitoring plans.

1) Endpoints Are the Trial’s Contract (And Mistakes Cost Years)

Every clinical trial is built around a claim, and the endpoint is the exact place where that claim becomes testable. The protocol can be perfect on paper, but if the endpoint is vague, hard to measure, or easy to distort, the entire study becomes a high budget argument with no conclusion. This is why experienced monitors and lead coordinators obsess over endpoint definitions, visit windows, and what “counts” as an event. A clean endpoint is not just a statistic. It is a system that connects eligibility, randomization, measurement, CRF design, monitoring, and analysis into one consistent story.

In real trials, endpoint failure rarely looks dramatic. It looks like small site level behaviors that quietly change the outcome. A rater uses a different scale version, a lab runs a non standardized assay, a coordinator documents outcomes in notes instead of the eCRF, or a sub investigator interprets “progression” differently from the central reader. These problems often show up late, when leadership starts asking why data is noisy and why the effect size is shrinking. If you work in site operations, you have seen how endpoint confusion becomes deviations, queries, and rework. That is why understanding trial mechanics like case report form (CRF) definition, types, and best practices matters as much as understanding the medical science.

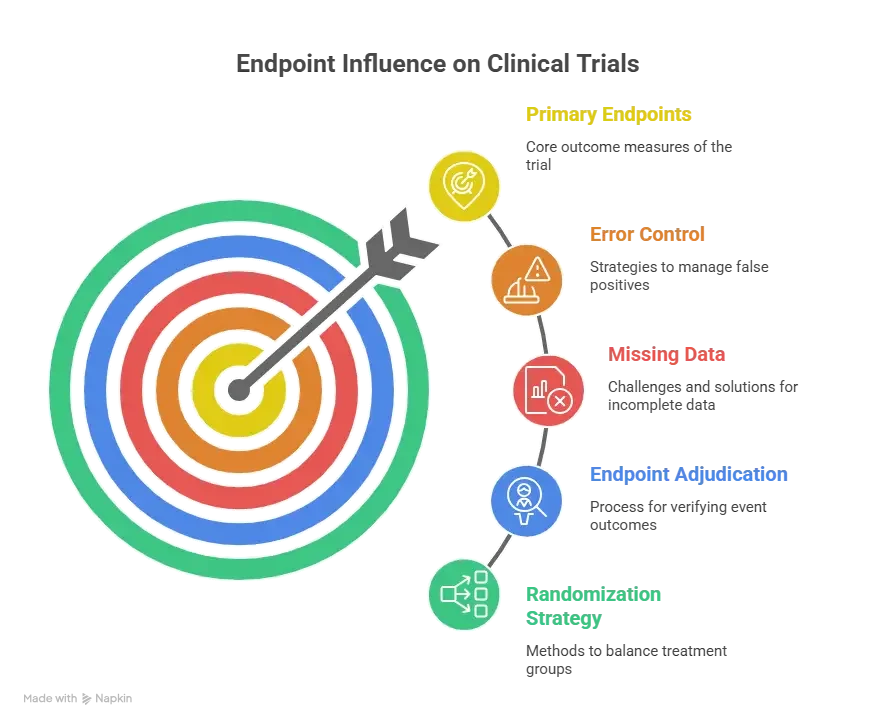

Endpoints also drive training burden. If the endpoint relies on complex assessments or strict timing, you will need tighter site selection, better rater training, clearer monitoring triggers, and stronger documentation discipline. This connects directly to how a clinical research coordinator (CRC) works and how a clinical research associate (CRA) monitors. Even the randomization approach, including whether you use blocks or stratification, can interact with endpoint interpretation, which is why endpoint planning often references randomization techniques in clinical trials explained clearly.

A strong endpoint strategy prevents the most painful scenario in clinical research: finishing a trial that “looks interesting” but cannot support a defensible conclusion. That is also why sponsors tend to promote people who can connect endpoint design to operational reality, whether that is a lead clinical research coordinator, a clinical trial manager, or a clinical research project manager. Endpoint clarity is not academic. It is career leverage.

2) Primary vs Secondary Endpoints: The Real Difference (Hierarchy, Power, and Consequences)

A primary endpoint is the main question the trial is designed to answer. It is where the trial’s statistical power is concentrated, where the type I error control is centered, and where the sponsor expects the headline conclusion to live. If the primary endpoint fails, it usually does not matter how beautiful the secondary endpoints look. That is the brutal truth of hierarchy. Secondary endpoints can strengthen the story, explain the mechanism, show patient meaningful benefits, or support labeling conversations, but they rarely rescue a failed primary without preplanned statistical strategy.

The cleanest way to remember the difference is this: the primary endpoint is what you are willing to bet the entire study on. The secondary endpoints are what you want to learn if the primary succeeds, and what you want to understand even if the primary is borderline. This is not about importance in a human sense. A secondary endpoint might be more meaningful to patients. But in the trial’s contract, the primary endpoint is the formal decision point.

This hierarchy creates immediate operational consequences. The measurement quality bar for the primary endpoint is higher. If a site is sloppy with primary endpoint data capture, that site is not just generating queries, it is risking the trial’s ability to detect the effect it is powered for. That is why CRAs will escalate primary endpoint issues faster and why central monitoring plans often include triggers for primary endpoint missingness, visit window deviation, and outliers. These patterns are often caught through CRF logic, which links back to CRF best practices and the monitoring discipline described in a CRA career guide.

Statistically, the primary endpoint is typically tied to the sample size calculation. That means your assumptions about effect size, variability, event rate, or response rate are translated into the number of participants required. If those assumptions are wrong, the trial becomes underpowered or inefficient. Secondary endpoints are often not powered the same way, which is why secondary signals can be unstable. They can look positive by chance, especially when many are tested. This is where multiplicity becomes a real threat. If you test many endpoints without a plan, you will eventually “find something,” but you risk finding noise, not truth. Multiplicity planning depends on biostatistical logic, and it helps to understand basic concepts described in biostatistics in clinical trials.

There is also a hidden pain point that hits real teams. The more endpoints you add, the more you increase visit burden, rater burden, data entry workload, and query risk. A trial can become operationally fragile. A CRC team that is already stretched can miss windows, mis file source, or under document endpoint related events, which connects back to real world site pressure covered in CRC responsibilities and certification and the workflow reality of a clinical trials coordinator pathway.

A final detail that separates strong protocols from weak ones is endpoint definition precision. A good endpoint definition includes what is measured, how it is measured, when it is measured, and how missing data is handled. It often clarifies whether the endpoint is assessed at a visit, over a time window, or as a time to event. It defines response thresholds, adjudication rules, and confirmation requirements. If a protocol does not define these, sites will define them themselves. That is how inconsistencies become “protocol compliant” because the protocol never pinned down the truth.

3) Choosing Endpoints That Survive Reality (Clinical Meaning, Feasibility, and Data Integrity)

Strong endpoint selection begins with a ruthless question: can this endpoint be measured consistently across all sites, across all participants, under real operational pressure. It is easy to propose endpoints that sound impressive. It is harder to pick endpoints that remain clean when coordinators are overloaded, devices fail, participants miss visits, and investigators interpret criteria differently. This is where experienced clinical operations leaders win, because they design endpoints that survive real life.

Clinical meaningfulness comes first. An endpoint should reflect a benefit patients and clinicians care about, not just a biomarker that moves. Biomarkers can be valuable, but they are often best positioned as secondary or exploratory unless they are strongly validated. When a biomarker is primary, the protocol must explain why the biomarker is a valid surrogate for clinical benefit and how the measurement will be standardized. If the endpoint is patient reported, you must plan for compliance, language versions, training, and missingness. If the endpoint is imaging based, you must plan for central reads, assessment timing, and adjudication. If the endpoint is event based, you must plan for event capture, follow up, and consistent definitions.

Feasibility is the part teams underestimate. If your endpoint needs a specialized assessment, ask whether every site can do it at the same quality. If not, either restrict sites or revise the endpoint. If your endpoint depends on strict timing, ask whether the visit schedule and participant population allow it. If participants have chaotic lives, tight windows will create missingness. Missingness is not just an annoyance. It can bias results and reduce power. This is where monitoring and site training connect directly to endpoint success, and why roles like clinical research monitor roadmap and senior CRA advancement emphasize proactive risk detection.

Data integrity is where endpoints live or die. An endpoint is only as credible as its source documentation chain. If sites document endpoint critical data in narrative notes without structured fields, you will get inconsistency. If the eCRF does not guide entry, you will get interpretation drift. If the protocol uses vague language like “clinically significant improvement,” you will get site to site variability. Endpoint planning must therefore be tightly connected to CRF design, source templates, and monitoring checks, which is why CRF best practices is not optional reading for endpoint heavy studies.

A practical method used by strong teams is the endpoint stress test. Before finalizing endpoints, they map each endpoint to: who measures it, where it is documented, what device or instrument is used, what training is required, what the acceptable visit window is, what happens if a visit is missed, and how the endpoint is adjudicated. They also test how the endpoint interacts with randomization and stratification. For example, if you stratify by baseline severity, you must ensure baseline severity is measured consistently. That ties directly to robust allocation planning described in randomization techniques explained clearly.

When endpoint planning is done well, it reduces site pain. Less rework. Fewer deviations. Cleaner monitoring visits. More confident interim updates. That translates into faster close out and fewer desperate protocol amendments. For the sponsor, it translates into a result that can be defended. For the site, it translates into a trial that is manageable. For your career, it positions you as someone who can prevent expensive mistakes, a skill that matters whether you aim for clinical trial manager or clinical operations manager.

4) What Endpoints Do to Your Stats and Operations (Power, Multiplicity, and Bias)

Primary endpoints dictate how the trial’s error control is structured. The simplest case is one primary endpoint with one primary comparison. But many trials involve multiple arms, multiple time points, or multiple primary endpoints. Each added comparison increases the chance of false positives unless you adjust. This is why secondary endpoint success can be misleading. If you test many secondaries without a strict plan, you can produce a highlight reel that is statistically fragile. Sponsors get burned here when press releases lean on secondaries after a primary miss. Experienced teams plan hierarchy, alpha allocation, and analysis sequencing from the start. Even if you are not a statistician, you should understand the practical implication explained in biostatistics in clinical trials.

Endpoints also drive missing data risk. Time to event endpoints handle some forms of missingness better than repeated measures, but they have their own traps, like censoring and event ascertainment bias. Repeated measure endpoints are sensitive to visit timing, dropout, and non adherence. Patient reported endpoints are sensitive to diary compliance and language. Imaging endpoints are sensitive to scheduling. If your endpoint is hard to collect, your missingness will not be random. That matters, because missing not at random can bias treatment effects. This is where operational leadership must collaborate with data management, CRF design, and monitoring to reduce missingness at the source, linking again to clinical data manager roadmap and clinical data coordinator responsibilities.

Another operational reality is endpoint adjudication. For event endpoints, adjudication can improve consistency, but it adds timelines, workload, and dependency on clean source documents. If sites do not document events cleanly, adjudication becomes guesswork. That is where the CRA has to push for better source, and where the CRC has to anticipate what documents will be needed. This is practical monitoring work, discussed broadly in the CRA roles and skills ecosystem.

Endpoints also affect randomization strategy. If your endpoint is highly sensitive to baseline severity or site behavior, stratification can help balance, but it can also create complexity. Too many stratification factors can make data entry error prone and increase allocation risk. This is a direct interaction between endpoint choice and randomization technique. Teams that treat randomization as separate from endpoints often pay later through imbalance narratives that undermine confidence.

Finally, endpoints shape how monitoring finds issues early. If your primary endpoint is a lab value, central monitoring can track distribution shifts and outliers. If your primary endpoint is a scale, monitoring must track rater variability and suspicious patterns. If your primary endpoint is an event, monitoring must track follow up completeness and event reporting lag. A strong monitoring plan is endpoint specific, and that is why experienced professionals evolve into clinical operations manager roles.

5) Practical Examples You Can Reuse (Protocol Language, Endpoint Maps, and Clean CRF Alignment)

If you want to upgrade your endpoint strategy quickly, build an endpoint map. An endpoint map is a simple internal document that lists each endpoint, its definition, its measurement method, its timing, its source documents, its CRF fields, and its analysis population. When teams do not build this map, the protocol, CRF, and monitoring plan drift apart. That is how you get the classic problem where the protocol says one thing, the CRF collects something slightly different, and the analysis team has to reconcile later. This is exactly why endpoint planning must reference CRF definition and best practices.

Here is what strong primary endpoint language looks like in practice. It is not vague. It locks down details.

Primary endpoint example wording: “Change from baseline to Week 12 in mean seated systolic blood pressure, measured using standardized automated device after five minutes rest, average of three readings, collected within the Week 12 visit window of day 77 to day 91.” This kind of language prevents sites from improvising. It also gives monitors a clear checklist. That is what reduces deviations.

Secondary endpoint wording should be equally clear, but it should also respect hierarchy. A common mistake is writing secondary endpoints that look like co primary endpoints, then treating them like primaries in presentations. If a secondary endpoint is intended for supportive evidence, specify that in the SAP. If it is exploratory, say so. If it will be part of a hierarchical testing procedure, specify order. Otherwise, you risk a situation where secondaries become marketing claims rather than defensible results.

Examples that work well in real protocols often combine an objective primary with meaningful secondaries. For instance, a primary endpoint might be a time to event or a standardized score, while secondaries include patient function, quality of life, and safety. The secondaries translate the primary into real world meaning. But this only works if secondaries are measured cleanly and not drowned in missing data. That means operational planning, training, and data management alignment, which is why career paths like lead clinical data analyst and clinical trial assistant career guide matter. These roles keep the machine running.

If your trial involves safety heavy questions, endpoint planning must also integrate pharmacovigilance. Safety endpoints are often secondary, but they are not secondary in importance. They influence benefit risk interpretation. Clean safety capture requires consistent reporting, seriousness classification, and follow up completeness, which connects to what is pharmacovigilance and career paths like pharmacovigilance associate roadmap and drug safety specialist guide.

One more operational template that boosts endpoint success is a “primary endpoint protection plan.” It includes: standardized training for the primary endpoint measure, a central review or calibration process where relevant, CRF edit checks that prevent incomplete entry, monitoring triggers for missingness and outliers, and a documented escalation pathway. This is how senior teams prevent last minute panic. It is also how you build credibility as a monitor or coordinator, whether you are growing as a clinical research assistant or aiming for clinical research administrator.

6) FAQs: Primary vs Secondary Endpoints (High Value Answers)

-

Primary endpoint is the single main outcome that determines whether the study’s main claim succeeds. Secondary endpoints are additional outcomes that add context, explain benefit, measure durability, or support safety and patient experience. For site teams, the key is hierarchy. Primary endpoint data must be collected with zero ambiguity, because it is tied to powering and headline interpretation. Secondary endpoints still matter, but they do not carry the same statistical weight unless the protocol specifies a formal hierarchy. Align endpoint collection with CRF structure using CRF best practices and ensure monitoring expectations are clear like in CRA roles.

-

Yes, but every additional primary endpoint increases complexity. Multiple primaries can be justified when the disease requires more than one dimension of benefit, such as symptom improvement plus functional improvement. The challenge is statistical. You must control for multiplicity, define success criteria clearly, and avoid creating a situation where success becomes ambiguous. Operationally, multiple primaries raise training and data quality risk. If sites struggle to measure one primary cleanly, two primaries can become a disaster. If you are considering this design, it is worth understanding basic error control concepts described in biostatistics in clinical trials and how endpoint complexity interacts with randomization strategy.

-

Because secondary endpoints are often not powered the same way, and because testing many endpoints increases the chance of finding something that looks significant by chance. Another reason is measurement quality differences. Sometimes the primary endpoint is harder to measure and has more noise, while a secondary endpoint is cleaner and shows a signal. But unless the analysis plan supports claims through a preplanned hierarchy, a positive secondary after a primary failure is usually considered hypothesis generating. This is where teams get trapped by wishful interpretation. To avoid that trap, ensure the protocol, CRF, and SAP align, using principles from CRF best practices and monitoring discipline covered in CRA career guidance.

-

Clinically meaningful means the endpoint reflects a change that matters to patients, clinicians, or healthcare decision makers. A lab value can be measurable and still not meaningful unless it reliably predicts benefit patients feel. Patient centered outcomes can be meaningful but hard to measure consistently. The best endpoints balance meaning with feasibility. They are defined precisely, measured consistently, and linked to real world benefit. Many teams use a layered approach: an objective primary endpoint supported by patient reported and functional secondary endpoints. To operationalize this, you need strong site processes like those described in CRC responsibilities and strong monitoring behaviors like those described in CRA roles.

-

Most endpoint related deviations come from unclear definitions, missed windows, inconsistent measurement procedures, or documentation gaps. Auditors and regulators care because endpoint inconsistency can create bias. A common audit pain point is when source does not support the endpoint captured in the CRF, or when the protocol definition is not followed consistently. Prevention requires endpoint specific training, source templates, and CRF alignment, anchored in CRF best practices. It also requires monitoring that focuses on endpoint critical processes, which is central to the CRA role.

-

They choose endpoints based on theory rather than site reality. They assume sites can measure complex outcomes without heavy training, they underestimate missing data risk, and they overload the study with endpoints that inflate workload. Another major mistake is treating endpoint selection as separate from randomization and data management. In reality, endpoint sensitivity can demand stratification, adjudication, or central review, all of which change operations. If you want a fast upgrade, build an endpoint map that ties each endpoint to CRF fields, source documents, and monitoring triggers. This is exactly the kind of cross functional competence that pushes people toward roles like clinical trial manager and clinical operations manager.

-

Even when the primary endpoint is efficacy, safety outcomes can determine whether the benefit is acceptable. Safety endpoints often include adverse event rates, serious adverse events, and discontinuations, and they can shift the interpretation of a positive efficacy result. Clean safety capture requires consistent reporting and follow up, which connects directly to what pharmacovigilance is and roles like drug safety specialist. In practical terms, endpoint planning should include clear rules for how safety data will be collected and how it will be summarized alongside efficacy, so the final story is credible, not selective.