Randomization Techniques in Clinical Trials: Explained Clearly

Randomization is the moment a clinical trial earns the right to be trusted. If allocation is predictable, biased, or poorly executed, every downstream deliverable becomes fragile. Regulators question your endpoints, statisticians fight imbalances, monitors chase deviations, and your team loses months defending decisions that should have been airtight. This 2026 guide explains randomization techniques in plain language, then goes deeper into what actually breaks in real studies. You will learn how to choose the right method, implement it cleanly, and document it so your trial stays credible under scrutiny.

1) Randomization in Clinical Trials: The Real Purpose (Not the Textbook Version)

Randomization exists to protect your trial from people. Not just bad actors. Normal people doing normal things under pressure. Sites that unconsciously enroll “healthier” patients into the arm they believe is better. Coordinators who schedule visits differently based on perceived treatment. Investigators who interpret borderline symptoms with subtle bias. If you have ever seen messy outcomes and finger pointing between operations and stats, randomization was often part of the root cause, along with weak documentation and controls that a strong quality assurance career mindset would have flagged early.

In 2026, randomization is also about operational resilience. Trials are more distributed, enrollment is more competitive, and datasets are more auditable. If your randomization design is too complex, sites will make errors and you will drown in deviations. If it is too simple, you risk imbalances that make your results less persuasive and less publishable.

Randomization delivers three outcomes that matter in real trials:

Comparability: Arms are similar enough that differences in outcomes can be attributed to treatment, not patient mix. This is deeply connected to clean data pipelines, which is why PV, safety, and data teams work best when aligned with roles like a clinical data manager and a lead clinical data analyst.

Protection from selection bias: Investigators cannot consistently predict the next assignment. When this fails, your study can look randomized on paper but behave like a biased observational study in practice.

Defensibility under inspection: You can explain how allocation worked, how it was concealed, and what happened when errors occurred. If you want to think like an inspector, read the discipline baked into proven test taking strategies for clinical research exams and apply that same structure to your trial documentation.

A common pain point is that teams focus on “which randomization method” and ignore “how will it be executed at sites.” Execution is where credibility dies. If you are on the operations side, pairing your randomization design with the realities explained in the clinical trial assistant career guide and the clinical research assistant roadmap will save you from preventable chaos.

2) Randomization Techniques Explained Clearly (When to Use Each One)

The “best” randomization method is the one that matches your sample size, risk of predictability, prognostic factors, and operational reality. If you choose a method that your sites cannot execute consistently, you will pay for it through deviations and rework that crushes timelines, exactly the kind of program risk discussed in broader leadership tracks like a clinical research administrator pathway and salary linked roles like a clinical research project manager guide.

Simple randomization

This is the classic “coin flip” approach. It is clean and defensible, but it assumes your sample size is large enough that chance imbalances average out. If you run a smaller trial and you end up with arms that differ on baseline severity or age, you will spend months explaining why your results should still be trusted, especially when safety and outcome patterns start to look uneven. That kind of downstream credibility challenge touches multiple teams, from clinical data management to safety reviewers who live inside aggregate patterns similar to the thinking in pharmacovigilance management.

Block randomization

Blocks keep the arms balanced as enrollment progresses. This matters when your trial is vulnerable to time effects. A new site comes online, a competing trial opens, a referral pattern changes, and suddenly enrollment is not stable. Blocks protect against that drift.

The risk is predictability. If the block size is fixed and staff learn it, the last allocation in a block can become guessable. Guessability is not a theoretical issue. It is how selection bias sneaks in while everyone still believes the trial is randomized. That is why strong teams use variable block sizes and central allocation, supported by inspection readiness principles you see in QA specialist roadmaps and even the discipline of structured rule thinking in clinical exam test strategies.

Stratified randomization

If you know certain baseline factors strongly predict outcome, you can stratify on them so each arm gets a similar mix. Typical examples are disease severity, region, or prior therapy. This is high value when your endpoints are sensitive and your sample size is not huge.

The failure mode is “stratify everything.” Teams get ambitious and create too many strata, then each stratum has too few participants, which reduces the benefit and increases complexity. Complexity creates site errors and data entry delays. If you want to reduce those errors, align your stratification plan with the realities described in the clinical data coordinator path and the operational pressure points that CTAs learn early in the clinical trial assistant guide.

Minimization

Minimization is a dynamic method that allocates the next participant to the arm that best improves balance across multiple covariates. It is powerful for smaller trials or when you have several prognostic factors. It is also misunderstood. People assume it is not “random enough.” In practice, it can be designed with a random element and defended well if documented correctly.

The real risk is operational timing. Minimization depends on accurate covariate entry at the moment of randomization. If sites enter baseline data late or inconsistently, your allocation logic runs on flawed inputs. That is why minimization demands tight workflow controls and clean systems, the kind of coordination mastered by strong data leads like a lead clinical data analyst and inspection focused roles like a clinical regulatory specialist.

Adaptive methods

Response adaptive randomization and Bayesian adaptive approaches are more common in modern platform trials and complex settings. They can increase the chance participants receive better performing arms. They also create risk if outcomes are delayed, data quality is weak, or the operational infrastructure cannot support fast reliable updates.

If you are considering adaptive methods, you must assume your trial will be challenged on transparency. You will need stronger documentation, stronger governance, and stronger cross functional discipline. Learn how clinical research governance behaves from role perspectives like regulatory affairs specialist pathways and leadership focused structures like a clinical research administrator role.

3) Allocation Concealment, Blinding, and Systems: Where Randomization Breaks in Real Life

A trial can have an excellent randomization method and still fail if allocation is not concealed. Allocation concealment is the barrier that prevents sites from predicting the next assignment. Without it, selection bias becomes likely, even if nobody intends to cheat.

Allocation concealment is operational, not theoretical

Common breakdowns look like this:

Sites “pre randomize” to plan inventory and appointments.

Staff delay enrollment when they suspect the next allocation will not favor their preferred arm.

Local spreadsheets or unapproved tools reveal patterns.

Fixed blocks become recognizable over time.

In 2026, the safest default is centralized randomization with audit trails. That usually means IRT systems or similar controlled workflows integrated into your trial operations.

If you want to map the technology landscape that supports clean data flow and monitoring, use internal CCRPS resources like the EDC platforms buyer guide and the remote monitoring tools list. If your team does not understand the operational impact of tooling, you end up with “randomization designed by stats” and “randomization executed by exhausted humans,” which is how mistakes multiply.

Blinding depends on randomization discipline

Blinding fails when allocation information leaks. Leakage can happen through obvious channels like unblinded drug packaging, but it also happens through subtle channels:

Staff infer assignment from visit frequency.

Certain lab monitoring requirements reveal treatment.

Side effect profiles reveal likely allocation.

Unbalanced randomization creates patterns that investigators notice.

A painful truth is that weak randomization discipline makes blinding harder to maintain. If you want to understand how these controls become inspection questions, pair your thinking with compliance oriented paths like QA specialist roles and regulatory affairs associate development.

Randomization and safety workflows intersect more than teams admit

When allocation errors occur, safety data interpretation becomes messy. A serious event in the wrong arm creates confusion and delays. It can also trigger incorrect reporting decisions if teams do not reconcile allocation quickly. That is why safety minded teams link randomization integrity to the same rigor they apply in drug safety specialist work and broader safety strategy paths like pharmacovigilance management.

If you want your documentation and workflows to hold up under pressure, build the same habits you would use to pass rigorous exams. Internal CCRPS resources like creating a strong study environment and test taking strategies are not just for learners. They are models for consistent performance under timelines.

4) Common Randomization Pitfalls (And the Fixes That Actually Work)

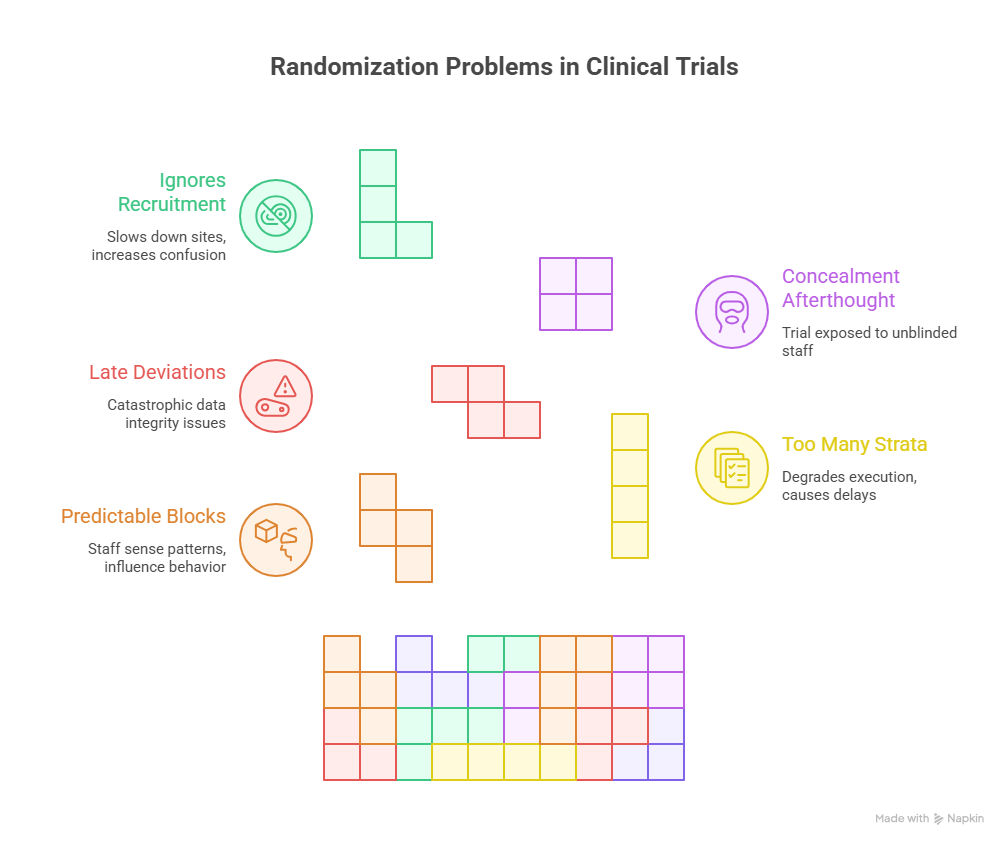

Randomization problems rarely start with statistics. They start with workflow. Here are the most common failures that burn trials and what to do about them.

Pitfall 1: Fixed blocks that become predictable

If your blocks are fixed and a site enrolls quickly, staff start sensing patterns. Even if they do not consciously manipulate, predictability can influence behavior. The fix is variable block sizes plus strict concealment. Also, never over explain the block structure in site level materials. Give sites only what they need to execute correctly.

This is where cross functional collaboration matters. Monitoring teams should be trained to spot predictability behaviors, and QA teams should review access controls. If you are building your career in this lane, the skill set aligns strongly with a QA specialist roadmap and regulatory accountability roles like a regulatory affairs specialist.

Pitfall 2: Too many stratification factors

Stratification feels like “smart design,” but it can degrade execution. The more strata you create, the more likely sites enter one baseline factor late, triggering randomization delays or incorrect allocations. The fix is ruthless prioritization. Choose only the factors that meaningfully affect outcome. Then simulate expected enrollment so you do not end up with empty strata.

This is also a data governance issue. If baseline covariates drive randomization, they become critical data. Your data operations must treat them as high priority. That is why understanding data roles like clinical data coordinator and clinical data manager directly improves trial execution.

Pitfall 3: Randomization deviations that are discovered late

Late discovery is what makes deviations catastrophic. If the wrong participant receives the wrong allocation and it is found weeks later, you now have data integrity issues, safety interpretation issues, and sometimes consent issues.

Fixes that work:

Build reconciliation checks between the randomization system and EDC.

Train sites on what to do when errors happen.

Require immediate documentation and escalation pathways.

Monitor deviation trends by site and address patterns early.

If you want a broader view of how trial teams prevent this kind of risk, look at program leadership paths like clinical research administrator roles and the vendor oversight ecosystem explained in the CRO vendor solutions guide.

Pitfall 4: Treating concealment like an afterthought

Concealment should be designed in from protocol to system access to training. If unblinded staff can see allocation sequences, or if sites use local logs, your trial is exposed. The fix is strict role based access, centralized assignment, and audit trails. This is also where remote monitoring tools can help spot behavior patterns early, which is why teams consult resources like the remote monitoring tools guide.

Pitfall 5: Randomization that ignores recruitment reality

In 2026, recruitment pressure is intense. Trials compete for the same patients, and sites have limited bandwidth. If your randomization design creates extra steps, more calls, and more confusion, sites will slow down. The fix is aligning design with site reality and setting up a smooth execution environment, which is the operational discipline you see in site facing roles like a clinical trial assistant and a clinical research assistant.

5) A Practical 2026 Playbook: How to Choose the Right Randomization Method

To choose a method that works, you need a structured decision process that balances science and execution.

Step 1: Start with the trial risk profile

Ask three questions:

How sensitive is the endpoint to baseline imbalance?

How fast will outcomes be observed?

How much operational complexity can sites handle?

If endpoints are sensitive and sample size is modest, stratified block or minimization often outperforms simple randomization in practice. If enrollment is large and stable, simple randomization can be defensible and easier to execute.

If your study is complex, use internal CCRPS salary and role context to map who should own what. For example, data integrity and reconciliation align with clinical data manager responsibilities, while inspection readiness aligns with QA specialist capabilities. When ownership is unclear, mistakes become “everybody’s problem,” meaning nobody fixes them quickly.

Step 2: Keep stratification minimal and meaningful

Use only a few high impact covariates. Disease severity is often justified. Region can be justified in global studies. Prior therapy can be justified in oncology and similar settings. If you stratify on five or six factors, you are begging for operational errors.

If your team wants more balance than stratification can safely provide, consider minimization. Minimization often gives better covariate balance with less explosion in strata.

Step 3: Design concealment like a system, not a note

You need:

Centralized assignment

Role based access control

Audit logs

Training that emphasizes what not to do

Monitoring signals that detect predictability behaviors

If you want to learn the technology ecosystem that often supports this, browse the EDC platforms list and integrate it with monitoring practices described in the remote monitoring tools guide. Strong systems reduce human errors, which is what you actually need.

Step 4: Simulate before you commit

A high value habit for 2026 trials is simulation. Simulate imbalance risk, predictability risk, and operational failure points. Test what happens if sites enroll unevenly. Test what happens when baseline variables are entered late. Simulate how often stratification cells will be empty.

This is the same mindset behind high performance preparation. You do not rely on hope. You rely on practice under realistic conditions, just like you would when using CCRPS study environment guidance and test taking strategies.

Step 5: Build a deviation response plan before the first patient

When randomization errors happen, teams often panic and improvise. That creates inconsistent decisions, which is deadly during audit. Pre define:

How deviations are documented

Who is notified

How corrective actions are tracked

How data is flagged

How safety implications are assessed

If you want to see how safety thinking is structured in clinical research, use role specific learning like the drug safety specialist guide and PV leadership thinking in the pharmacovigilance manager roadmap. Randomization errors are not only statistical issues. They can become safety interpretation issues quickly.

6) FAQs: Randomization Techniques in Clinical Trials

-

Randomization is the method used to assign participants to treatment arms. Allocation concealment is the operational protection that prevents sites from predicting assignments before enrollment. You can have a perfect randomization method and still fail if concealment is weak. Concealment is where selection bias enters. If you want to think like an auditor, align with inspection focused practices found in the QA specialist roadmap and regulatory role paths like the clinical regulatory specialist guide.

-

Block randomization is useful when you want balance between arms throughout enrollment, especially in smaller trials or when enrollment happens over time with potential shifts in patient mix. It is also useful when sites enroll at different speeds, because it reduces drift. The key is using variable block sizes and strict concealment so sites cannot guess the sequence. Operational discipline here often mirrors what strong site facing teams develop in the clinical trial assistant career guide.

-

In practice, more than a few stratification factors often becomes too many. The issue is not theory. It is execution. Too many strata create thin cells and make randomization dependent on baseline data being entered perfectly every time. That rarely happens at busy sites. If your team wants better balance than stratification can safely deliver, consider minimization and document it clearly. For the data side, the clinical data manager and clinical data coordinator perspectives help you design workflows that reduce errors.

-

Minimization is a valid allocation method and is widely used, especially when balancing multiple covariates in smaller trials. It can be implemented with a random element so assignments are not deterministic. The key is transparency. Document the algorithm, the variables, and the random component. Then show that the method was pre specified and executed consistently. If your team is worried about defensibility, adopt the documentation mindset found in regulatory affairs specialist pathways and QA inspection readiness.

-

Imbalance can happen because of chance in small samples, uneven site enrollment, missing baseline covariate data, or operational errors that lead to deviations. It can also happen when outcomes correlate with a factor you did not account for. The fix is to choose a method aligned to sample size, use minimal meaningful stratification or minimization, and monitor imbalances early. Monitoring and data systems matter here, which is why teams consult resources like the remote monitoring tools guide and the EDC platforms buyer guide.

-

If allocation errors occur, safety events may be attributed to the wrong arm, which can distort risk assessment. Even when allocations are correct, imbalances in baseline risk factors can make one arm appear less safe. That is why randomization integrity and clean reconciliation matter. Safety professionals learn this quickly in pathways like the drug safety specialist career guide and PV leadership tracks like the pharmacovigilance manager roadmap.

-

Document the method, any stratification factors, block size strategy if applicable, concealment approach, system access controls, audit trails, deviation handling procedures, and reconciliation checks between systems. Also document training materials and monitoring evidence that the process was followed. If you want to strengthen your documentation discipline, use the structured approach behind test taking strategies and building a strong study environment, because those habits map directly to consistent compliance performance.