Top Clinical Research Journals & Publications: Comprehensive Directory

Academic journals can either make you sharper every week or waste your time with noise. In clinical research, the gap between “I read papers” and “I use publications to make better trial decisions” is massive. A real directory is not just a list of famous titles. It is a system that tells you what to read, when to read it, how to judge it, and how to translate it into protocol and operations. This guide gives you that system plus a comprehensive publication directory you can use for CRA work, CRC execution, data quality, safety, and clinical operations.

1) What Makes a “Top” Clinical Research Journal Useful for Trial Work

A top journal is not automatically the best journal for you. For a CRA, the best journal is the one that improves monitoring decisions and site risk detection, which only matters if you understand the real expectations described in CRA roles and skills and the progression covered in the CRA definitive career guide. For a CRC, the best journal is the one that makes your source documentation, visit windows, and data entry cleaner, which connects directly to CRC responsibilities and practical execution in how to become a CRC.

A publication is useful when it helps you answer one of five questions fast.

1) Does this design hold up operationally? If the randomization approach, visit schedules, or endpoint capture demands are intense, you need to read it through a trial execution lens. Connect this to the realities explained in randomization techniques, because operational teams get burned when they misunderstand allocation and balance assumptions.

2) What are the endpoint and data implications? Journals often describe endpoints cleanly on paper, but the real world problem is whether your CRF and source flow can support them. That is why your reading should be anchored to CRF best practices and also to how teams manage data roles like the clinical data manager and clinical data coordinator.

3) What is the safety profile and monitoring burden? A study can look effective and still be operationally brutal because the safety monitoring plan is heavy. If you are reading safety driven papers, you need the core foundation covered in what is pharmacovigilance and you should understand the working reality of roles like a pharmacovigilance associate or drug safety specialist.

4) Can you trust the analysis? Even good journals publish studies that are overconfident in conclusions. Your defense is statistical literacy grounded in biostatistics in clinical trials, so you can spot weak assumptions fast.

5) What changes next week on a real study? This is the most important question. If a paper cannot be translated into site training, monitoring focus, or data quality controls, it is just interesting, not useful.

2) The Directory System: A Practical Way to Organize Journals and Publications

Most people fail at reading journals because they read randomly. A directory becomes powerful when it is tied to a workflow.

Bucket A: Decision journals. These are high influence general medical journals where pivotal trials shape practice and regulatory discussion. Use them to benchmark endpoint choices and overall trial framing. When you read a pivotal trial, map it back to operational roles like a clinical trial manager and a clinical research project manager, because those roles translate evidence into execution.

Bucket B: Therapeutic area journals. These are where operational details show up. Oncology journals highlight complex imaging schedules and response criteria. CNS journals highlight rater training risk. These journals are where CRCs and CRAs find the hidden workload that causes deviations and data drift, which is why the reading should connect to CRC responsibilities and monitoring focus built around CRA skills.

Bucket C: Methods journals. These teach you design and execution tactics. They help you understand topics like randomization, trial conduct, and pragmatic designs. Connect these readings to randomization techniques and to the analysis lens in biostatistics.

Bucket D: Safety and real world evidence publications. These teach how safety signals are detected, how post marketing evidence is interpreted, and how risk is communicated. They pair naturally with pharmacovigilance fundamentals and career tracks like pharmacovigilance manager.

Bucket E: Regulatory and quality publications. These are not “journals” in the traditional sense, but they define your compliance floor. If you ignore them, you read papers but still fail inspections. Tie this to what quality roles actually enforce like a quality assurance specialist and a clinical compliance officer.

If you organize your reading using these buckets, you stop consuming information and start building a trial decision advantage.

3) How to Read a Clinical Trial Paper Like a CRA, CRC, or Clin Ops Lead

A trial paper is a compressed story. Your job is to unpack what was hidden.

Start with the methods, not the conclusions. The abstract is marketing. The methods tell you what really happened. Read eligibility criteria and ask whether sites could execute it without constant protocol deviations. Then map that to what CRCs face daily in clinical research coordinator execution and the practical steps in becoming a CRC.

Next, isolate endpoint definitions and ask how they were captured. Endpoints that look simple can require complex CRF design, source workflows, and adjudication. This is where reading becomes operations. Use the framework in CRF definition and best practices and pair it with data execution roles like clinical data management and lead clinical data analyst progression.

Then assess randomization and allocation concealment implications. If the paper uses block randomization or stratification, ask what operational risks existed at sites. Poor concealment creates subtle bias and can create unblinding pressure. This is explained clearly in randomization techniques, and it is not theoretical. It affects real behavior.

Then evaluate safety. Do not just look at adverse event tables. Look at how AEs were collected, how serious events were handled, and whether monitoring intensity could be sustained. Connect this to the operational discipline in pharmacovigilance fundamentals and the practical career reality of a drug safety specialist.

Finally, use a statistics sanity check. You do not need to be a biostatistician, but you do need enough literacy to spot fragile conclusions. Anchor that literacy in biostatistics basics. This step protects you from repeating designs that look strong but fail in your population.

4) How to Avoid Predatory Journals and Bad Publications Without Getting Paranoid

Predatory publishing is not just a career problem. It becomes a trial risk problem when teams borrow claims from weak sources to justify endpoints, eligibility, or safety assumptions. The danger is not just fraud. The danger is low quality science that looks “published.”

Use these fast filters.

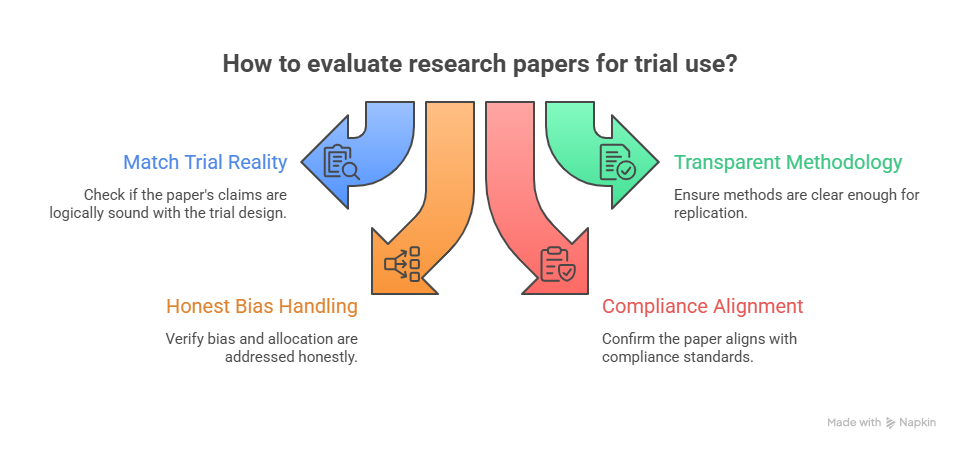

Filter 1: Does the paper match the trial reality? If a paper claims dramatic effects with small samples, check whether the design would survive the basic logic explained in biostatistics basics. If not, treat it as hypothesis generating only.

Filter 2: Is the methodology transparent enough to replicate? If methods are vague, endpoints are mushy, or data collection is unclear, it is not safe to translate into protocol operations. This directly connects to why CRFs matter. Use CRF best practices as a realism test. If you cannot imagine how data was captured, you cannot trust the conclusion.

Filter 3: Does the design handle bias and allocation honestly? Weak papers often hide bias behind technical language. A quick read of allocation and concealment concepts from randomization techniques helps you spot the common traps.

Filter 4: Does it align with the compliance world you live in? A paper can be scientific and still unusable if it ignores monitoring, documentation, and safety obligations. That is why quality and compliance content like clinical compliance officer responsibilities and audit framing in clinical quality auditor pathways matter even when you are “just reading journals.”

A smart approach is balanced. You do not need to distrust everything. You need a repeatable way to classify evidence into three buckets: practice changing, operationally informative, or hypothesis only.

5) Building a Reading Workflow That Actually Improves Trial Performance

The fastest way to become valuable on a study is to turn publications into operational improvements. Here is a workflow that works in real teams.

Step 1: Create a watchlist of 10 sources. Use two decision journals, three therapeutic area journals, two methods sources, two safety sources, and one registry. The directory table gives you options. Then add internal learning anchors so reading translates into your role, such as CRA skills, CRC responsibilities, and pharmacovigilance basics.

Step 2: Convert each paper into a one page “trial impact brief.” The brief has five sections: design summary, endpoint capture implications, safety monitoring implications, data and CRF implications, and the single biggest operational risk. This forces you to translate science into the real world of CRF workflows and the data backbone handled by clinical data managers.

Step 3: Tie reading to your next site visit or meeting. If you are a CRA, pick one insight that changes how you monitor, escalate, or train. That makes you more valuable than a CRA who only reports status, which is the difference between average and strong execution described across CRA career guidance and senior CRA insights. If you are a CRC, pick one insight that reduces deviations or data errors and aligns with what high performing CRCs do in CRC pathways.

Step 4: Build a small monthly evidence meeting. Keep it tight. One paper, one operational decision, one process update. If you run clinical operations, connect these decisions to roles like clinical trial manager and clinical operations manager so evidence becomes governance.

Step 5: Track impact. Track one metric that moves because of your reading. Lower query backlog, fewer deviations, faster follow up, cleaner CRFs. When you can point to impact, your credibility becomes real and your career accelerates.

6) FAQs: Top Clinical Research Journals and Publications

-

CRAs benefit most from journals that publish pivotal trials plus methods focused publications that expose operational risks. Your goal is not to memorize results. Your goal is to understand what trial designs demand from sites and how bias or poor execution can distort outcomes. Combine high influence journals with a methods source, then anchor your learning to what the CRA role actually requires as explained in CRA roles and skills and the career level expectations in the CRA definitive guide. Use each paper to refine what you check during monitoring and what you train at sites.

-

CRCs should prioritize therapeutic area publications that describe visit schedules, assessment timing, and endpoint capture realities, because those details drive the workflow at the site level. Then pair those journals with practical guidance on data capture and documentation such as CRF best practices so you can translate a paper into clean execution. If you want a role aligned path, connect this to CRC responsibilities and how to become a CRC.

-

You only need a few fundamentals to spot fragile conclusions. Focus on whether the outcome size is realistic, whether confidence intervals are wide, whether subgroup claims are overstated, and whether missing data handling is credible. Build this literacy using biostatistics in clinical trials. Then apply it consistently. If a paper feels “too good,” you are often right. This protects you from bringing weak evidence into protocol decisions.

-

Registries show the protocol level reality of what teams planned to do, not just the polished narrative in a paper. They expose endpoints, eligibility, arms, and timing in a way that helps you sanity check feasibility and competitor designs. Use registry information to anticipate operational burdens, then cross reference your planning with practical guidance like randomization techniques and documentation discipline from CRF best practices.

-

Safety professionals should track publications that focus on signal detection, case definitions, and real world evidence interpretation. Then anchor that reading to the operational foundations in pharmacovigilance essentials and role based execution in the pharmacovigilance associate roadmap and drug safety specialist guide. The goal is not to collect papers. The goal is to improve safety monitoring decisions and reconciliation quality.

-

Clin ops leaders should treat publications as inputs to risk registers and training plans. When a paper reveals a hard to execute endpoint or a design that increases site burden, that should directly influence monitoring focus, site selection, and training cadence. Tie this to governance roles like clinical trial manager and operational coordination in clinical research project management. Publications become valuable when they change what your teams do.

-

Use a two layer approach. For early signals, scan preprints carefully, but treat them as hypothesis only until peer reviewed. For decisions that affect protocols, rely on peer reviewed sources and registries, and sanity check methods using biostatistics basics and allocation logic from randomization techniques. If a paper cannot explain how data was captured cleanly, it is not safe to operationalize, which is why CRF best practices remain a powerful reality test.

-

Build a repeatable habit where each paper produces an operational artifact. A one page impact brief, a site training note, a monitoring focus update, or a data quality checklist. This immediately increases your value because you are not just informed, you are useful. Align that output with your role trajectory, whether that is the monitoring path in CRA career guidance, the site execution path in CRC responsibilities, or the safety track in pharmacovigilance foundations. Consistent translation beats random reading every time.